Essay by Terri C Smith

A Buddhist story, “The Moon Cannot Be Stolen” (Zen Koan #9) presents the moon as a celestial object that is available to everyone who gazes upon it, something that cannot be owned or stolen and that buoys any viewer’s inner life with its exquisiteness:

Ryokan, a Zen master, lived the simplest kind of life in a little hut at the foot of a mountain. One evening a thief visited the hut only to discover there was nothing to steal.

Ryokan returned and caught him. “You have come a long way to visit me,” he told the prowler, “ and you should not return empty-handed. Please take my clothes as a gift.”

The thief was bewildered. He took the clothes and slunk away.

Ryokan sat naked, watching the moon. “Poor fellow,” he mused, “I wish I could have given him this beautiful moon.”

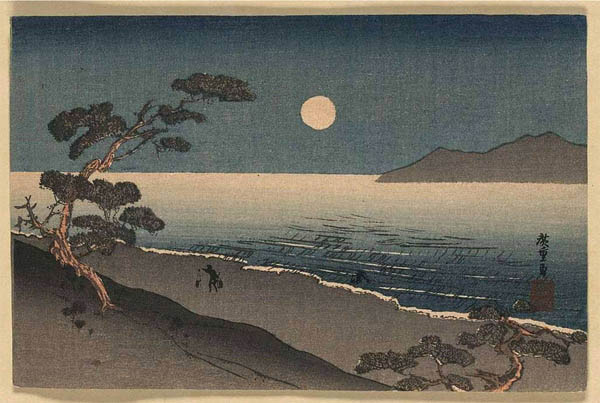

Figure 1: The Ukiyo-e Moon, 1866

Figure 1: The Ukiyo-e Moon, 1866Ryokan was saddened that the thief did not realize that the moon was also his and its light was available if the thief would only shift his perspective from one of earthly scarcity to one of spacious gratitude. This appreciation of the moon came to Japan in the 6th century when Buddhism was introduced and the sun and the moon began to appear in Japanese art (figure 1)[1]. “The moon played a key role in the arrangement of the monthly calendar all the way through the Edo period [1603–1868], and it was common for citizens to celebrate the moon by hosting moon viewing parties also known as Tsukimi,”[2] which “had come to be a popular practice even among commoners and was closely associated with autumn festival traditions involving thankful offerings of freshly harvested rice to the gods.”[3]

This idea of a shared moon that belongs to anyone who gazes upon it has sparked imagination across cultures, informing religion, science, and art. Prehistoric people documented the phases of the moon some 30,000 years ago with cave paintings and carvings, and many tribes of indigenous peoples tracked time using the cycles of the moon and the seasons. The moon also holds a sacred place in virtually every ancient culture, spawning deities, for instance: Inca’s moon goddess Mama Killa who was associated with “lunar cycles, timekeeping, fertility, agriculture, femininity, motherhood, cosmology, and divinity”[4]; Máni, a boy god who in Norse mythology was the moon personified and controlled its waxing and waning; and among peoples in the Philippines and the Americas, indigenous groups each had their own moon deities with unique names, stories, and functions. In the Philippines’ Pangasinense mythology, for instance, Bulan was “the merry and mischievous moon god, whose dim palace was the source of the perpetual light which became the stars [and who] guides the ways of thieves.”[5] In Native American groups, the Inuit people called their moon god “Igaluk,” the Pawnee called theirs “Pah,” and in the Navajo tribe their moon goddess was Yoołgai Asdzą́ą́ which means “white-shelled woman.”

Figure 2: Korean Moon Jar, Joseon Dynasty, 18th Century, Porcelain, Collection of the Honolulu Museum of Art

Figure 2: Korean Moon Jar, Joseon Dynasty, 18th Century, Porcelain, Collection of the Honolulu Museum of ArtAn intriguing decorative arts example of the moon’s influence is Korea’s “moon jars” (1392-1910), which have a surface of white opalescent porcelain and are named for their spherical shape that resembles a full moon (figure 2). According to Haely Chang, “The moon jar and its aesthetic became a cultural symbol of Korean art abroad, due not only to its beauty but also to its capacity to traverse formal, temporal, and geographical boundaries.”[6] In other words, the jars successfully mimicked the universal appeal of the moon itself.

Figure 3: Jan van Eyck, The Crucifixion; The Last Judgment, ca. 1436-1438, oil on canvas transferred from wood, Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

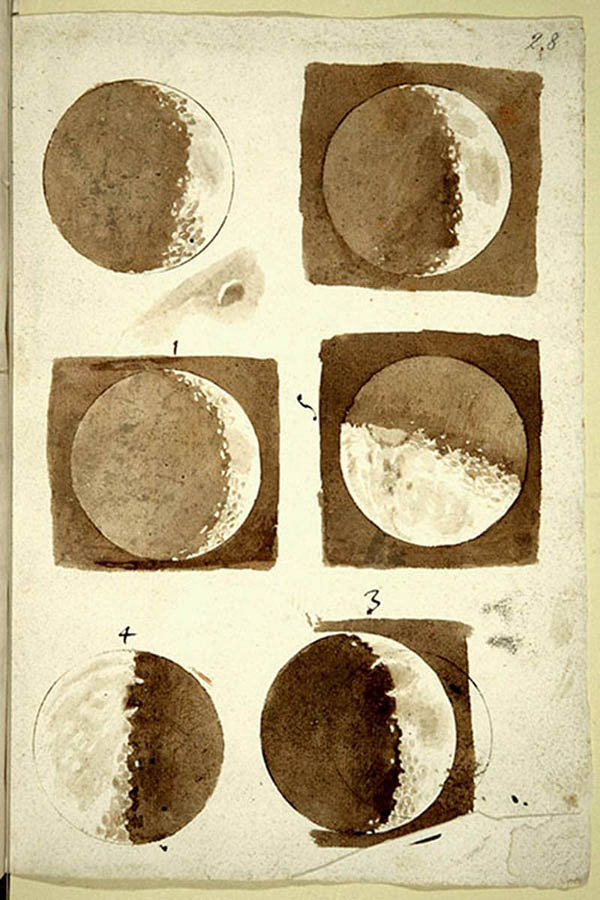

Figure 3: Jan van Eyck, The Crucifixion; The Last Judgment, ca. 1436-1438, oil on canvas transferred from wood, Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of ArtThe beginning of the Renaissance period in Europe corresponded with early moon jar production and its painters shifted how the moon was rendered in art. Prior to the Renaissance, writes Colleen Boyd “the moon was seen with…pre-scientific, pre-ocularcentric consciousness that perceived the external world through a complex filter heavily tinted with religion, mysticism, and metaphysics.” In other words, these early renderings of the moon, including those found in Edo period Japanese paintings, operate more like a signifier than a lifelike representation. Boyd cites Dutch painter Jan van Eyck’s 1441 painting The Crucifixion (figure 3) as one of the earliest paintings that “left behind the more simplified and symbolic representations of his predecessors” and “unveiled the moon in spectacular naturalistic clarity.”[7] In 1610, a date many publications mark as the last year of the Renaissance, Galileo made his first drawings (figure 4) of the moon informed by an improved telescope (at 20x magnification[8]). The drawings showed phases of the moon as he observed them from November 30 through December 18th. Galileo included renderings of craters and shadows that the telescope had revealed, upending the accepted world view of the moon as a perfectly smooth, heavenly white surface.

Figure 4: Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)Drawings of the Moon, November-December 1609, Collection of Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale

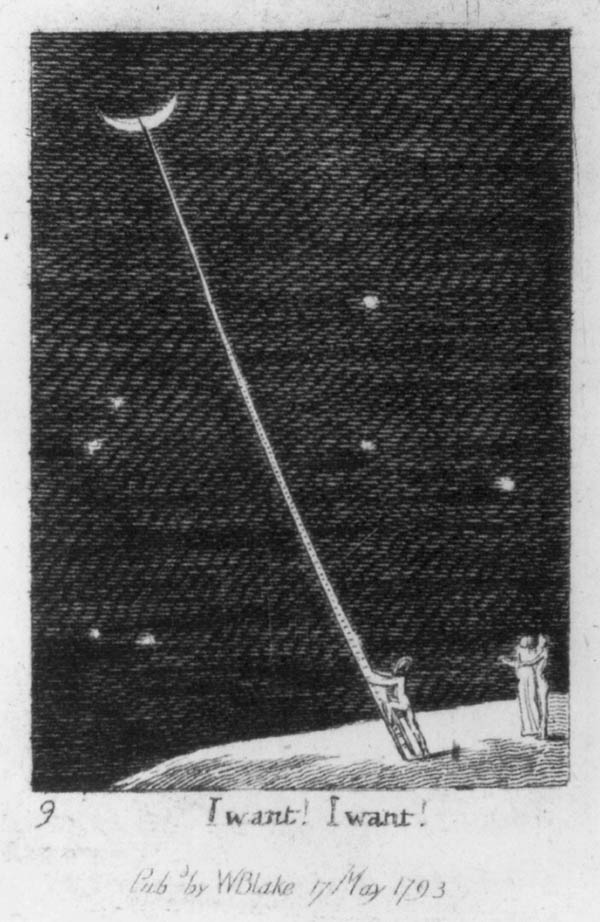

Figure 4: Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)Drawings of the Moon, November-December 1609, Collection of Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale Figure 4-1: William Blake (1757-1827)I Want! I Want!, 1793?, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

Figure 4-1: William Blake (1757-1827)I Want! I Want!, 1793?, Library of Congress Prints and PhotographsGalileo’s work informed and was a precursor to the foregrounding of science during The Age of Enlightenment (1685-1815), a movement that focused on empiricism and natural law, among other philosophies. William Blake—poet, artist, musician and philosopher—was a counter-enlightenment figure who in the midst of that age focused on individual divinity, creating texts and drawings that were mystical in nature. Blake has left a lasting influence on literature and art, and while there is no evidence that he was mentally ill, he “regularly [saw] God, angels and demons, and often spoke with the spirit of his dead brother Robert [and]…[a]s a result…he was deemed mad by much of 18th and 19th Century England, and died penniless and largely unheralded.”[9] His thinking about the moon was consequently out of step and had more in common with the British Romantic writers’ (1785 and 1832) appreciation of the sublime than the empiricism of scientific exploration. In an etching from 1793, published in his book For children: the gates of paradise, Blake featured three people standing on earth, with one of them (who seems to have some sort of helmet on) climbing a very tall ladder that leans against a crescent moon. In a text about this early book, Andrew Green wonders whether the etching[10] reflects Blake’s appreciation for “spiritual energy and ambition [and perhaps the drawing symbolizes] an attempt to escape from the oppressive gravity of the corporeal world”; or since the words under the image are “I want! I want!”, Green asks, “could the desire to climb to the moon stand for acquisitiveness, the soul-destroying urge to possess more and more, to master…more and more of the universe around us?”[11] A year later, in Songs of Innocence and Experience, Blake’s poem “Night” reads, “The moon, like a flower/In heaven’s high bower,/With silent delight, Sits and smiles on the night,” and “A Cradle Song” begins “Sweet dreams, form a shade/O’er my lovely infant’s head; Sweet dreams of pleasant streams/be happy, silent, moony beams,” personifying the moon as happy and smiling.

Figure 5: Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon, ca. 1825–30, oil on canvas, Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of art

Figure 5: Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon, ca. 1825–30, oil on canvas, Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of art Figure 6: Thomas Cole, Landscape (moonlight), ca. 1833–34, oil on Canvas, Collection of the New York Historical Society, New York, NY

Figure 6: Thomas Cole, Landscape (moonlight), ca. 1833–34, oil on Canvas, Collection of the New York Historical Society, New York, NY Figure 7: George Inness, Winter Moonlight (Christmas Eve), 1866, oil on Canvas, Collection of Montclair Art Museum

Figure 7: George Inness, Winter Moonlight (Christmas Eve), 1866, oil on Canvas, Collection of Montclair Art MuseumDuring the same era (1770-1830) the German romantic painters were also fascinated with the moon, but the style was more in keeping with van Eyck’s realism and they “regarded the motif as an object of pious contemplation,”[12] as in Casper David Friedrich’s (figure 5) “Two Men Contemplating the Moon” (1825-1830). Hudson Valley River School painters (1825-1870) in America also often included the moon in their landscapes in a representational, yet moody, style, as in Thomas Cole’s Landscape (moonlight), ca. 1833–34 (figure 6), Frederic Edwin Church’s Moonrise (1865), George Inness’s Winter Moonlight (Christmas Eve) (1866) (figure 7[13]), and Susie M. Barstow’s Night in the Woods (1890-91) (figure 8).

Figure 8: Susie M. Barstow, Night in the Woods, 1890, oil on canvas

Figure 8: Susie M. Barstow, Night in the Woods, 1890, oil on canvasDevelopments in technology (i.e., Galileo’s microscope and the Apollo missions) have affected how we know the moon but also how artists interpret it. Importantly, the invention of photography in 1839, allowed for painters to expand beyond representing the world in a realistic manner, leading to impressionism and giving early modernist painters—and later abstract expressionists—the latitude to render their perception of the world in a less literal manner, infusing images with the emotional, spiritual, and psychological. For artists like Arthur Dove and Charles Burchfield the moon was a perennial motif. Unlike van Eyck’s The Crucifixion, their moons pulse, swell, defy one-point perspective, and become glowing orbs more akin to Blake’s ideas of a spiritual light force—their ideas and feelings about the moon are what they convey. In Dove’s Through a Frosty Moon (1941) (figure 9[14]), the landscape and moon are so abstracted that, without the title, a viewer might find the Earth’s only satellite unrecognizable; however, the title clues the viewer in that the white oblong shape in the center signifies a moon, much like the name “white-shelled woman” or the Korean “moon jar.” Burchfield’s moons appeared in various phases (crescents, half, full, etc.) in dozens of watercolors. With his painting Sun and Rocks (1918–1950) the moon is a shadow, blocking the sun in a full solar eclipse and forming a cross with its rays, a symbolic extension of Burchfield’s Christian faith and his recent conversion to Lutheranism.[15] There are even examples of the moon as an influence in abstract art, including works by Wasilly Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Hans Hoffman, and Alma Thomas who, inspired by the space program, made a series of Earth and space paintings in the early 1970s.[16]

Figure 9: Arthur G. Dove, Through a Frosty Moon, 1941, oil and wax emulsion on canvas

Figure 9: Arthur G. Dove, Through a Frosty Moon, 1941, oil and wax emulsion on canvasConceptual artists of the 1970s also made work informed by the space program, most directly, there was a tiny ceramic tile that was drawn on by artists Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, David Novros, Forrest Myers, Robert Rauschenberg, and John Chamberlain and was reportedly attached to Apollo 12 spacecraft and left on the moon. Land artists like Robert Smithson also were inspired by images of the moon when they created otherworldly landscapes with dirt and rocks. Three of On Kawara’s minimalist paintings that feature crisply painted dates (month, day, year) were inspired by the moon landing. These “Moon Landing” paintings operated as signifiers of shared global events and featured three Apollo space mission dates: “July 16 was the day of lift-off; July 20 was the day when the shuttle landed; and on July 21, Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon’s surface for the first time.”[17] Guggenheim curator Jeffrey Weiss writes in the Museum’s blog that On Kawara kept clippings about space travel and felt that space exploration “has to do with the history of consciousness, which was a topic that he believed to be at stake in his work.” Feminist, activist artist Betye Saar, who was influenced in part by tarot and other forms of divination, often painted the moon in its pre-Renaissance function, as a signifier, in many of her assemblage works such as Black Girl’s Window (1969).

This of course is merely a snapshot of how the moon—as a map for time, spiritual symbol, and the Earth’s closest heavenly object (one that became explorable thanks to telescopic lenses, photography, satellites, and space travel)—metaphorically has launched a thousand ships in art, literature, science, and more. QLOCKTWO’s MOON clock is a time object that understands celestial archetypes in art, timekeeping, and—to borrow from On Kawara’s perspective—shared consciousness. According to its makers Marco Biegert and Andreas Funk, MOON is born from this universal fascination:

The moon has inspired mankind since time immemorial, it is a cultural mirror of society—shaping it for centuries. It has inspired artists and scientists throughout the ages, guiding their work and creativity. Different cultures have always developed their own scientific and artistic interpretations. At the same time, the brightest celestial body in our night sky has served mankind as a source of light—and always as a timepiece and calendar. Despite all spiritual, temporal and cultural differences, it connects us—that is something very special.[18]

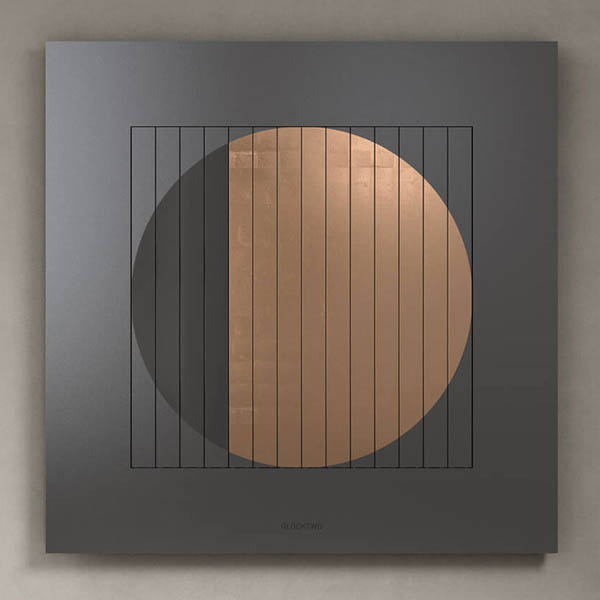

With MOON, a centered gilt disk—either made of 24k gold, platinum or “moon gold” (a combination of yellow gold and platinum)—shimmers and is paired with a backdrop (or “sky”) of “Dawn,” “Midnight,” or “Nightfall.” Using a one-dimensional (vs. perspectival) depiction with crisp, clean edges, the designers invoke renderings of the moon as a symbol, reminiscent of the circle moons in Edo-era Japanese art. While it carries with it aspects of the pristine, smooth moon that was disabused by Galileo’s drawings, the shifts in reflection in the alloy intimate the craters and shadows Galileo drew in 1610.

Figure 10: QLOCKTWO, MOON, 2023, aluminum, wood, metal leaf, electronic and mechanical components

Figure 10: QLOCKTWO, MOON, 2023, aluminum, wood, metal leaf, electronic and mechanical componentsMOON is kinetic and, using triangular prisms, the moon’s phases are replicated as gold bars flip out of view (facing the interior of the structure) throughout the month mimicking the waning moon where less of the sphere is illuminated with the passage of time; and then after the lunar cycle of 28 days, the moon begins to wax as vertical gold bars are added over time, culminating in a full moon. While metaphysical and historical aspects of the moon inform QLOCKTWO’s time object, the science of the moon’s cycles and of timekeeping are intrinsic to its art and function. Kinetic art and its histories (i.e., Alexander Calder’s mobiles and Jean Tinguely’s Dada-influenced moving sculptures and drawing machines) combine with precision timekeeping in MOON, which accurately animates celestial cycles.

QLOCKTWO’s designers share that they “don't actively seek inspiration from other designers,” but instead “observe the world, question everything, and strip ideas down to their absolute essence.” Yet, through an art historical lens, contemporary art movements can be teased out when viewing MOON. The square shape, the precision with which the moon is rendered as a perfect circle, and the matt ground, bring to mind color field (1940s-1950s) and hard edge (late 1950s-1970s) painting. Color field painter Kenneth Noland, for instance, created a series of square paintings with a centered circle like The Gift (1961-1962) and Drought (1962). Noland’s paintings were influenced by artists including Paul Klee and Joseph Albers, additionally “the glowing abstracted landscapes of Arthur Dove (for instance Me and the Moon 1937)...or the radiating bands in Georgia O’Keeffe’s Red Hills, Lake George 1927 suggest…sources for Noland’s circle paintings.”[19]

With MOON, triangular prisms allow for a third glossier surface to represent the shadow of the moon during the 28 day cycle. This combination of a matt and glossy in the same color (figure 11), are reminiscent of the subtle differences between blacks in Ad Reinhardt’s black on black paintings (1953-1967) where, while he did not use glossy colors, he did use very dark versions of blues, reds, etc., so that “[w]hat at first appears to be an unmodulated, all-black square reveals its tonal nuances and somber variations only after sustained, attentive viewing.”[20] More recently, the light artist James Turrell (b. 1943) has built and cut into existing rooms called “Skyspaces” to create sky vistas that nudge viewers to look more deeply at the subtle changes of celestial events, especially sunrise and sunset, when the sun and moon change places. “[A]ll of Turrell’s skyspaces harken back to ancient building techniques that deployed natural light—and the cycles of the cosmos—to create symbolic architecture,”[21] and according to Turrell, “In this stage set of geologic time, I wanted to make spaces that engage celestial events in light so that the spaces perform a ‘music of the spheres’ in light.”[22]

Figure 11: Triangular prisms represent shadow and reflected light on QLOCKTWO's MOON

Figure 11: Triangular prisms represent shadow and reflected light on QLOCKTWO's MOONWith MOON, QLOCKTWO creates a kinetic, portable artwork that tracks time, merging the archetypes of moon as symbol, moon as timekeeper, and moon as lyrical companion. Biegert and Funk elaborate on what MOON brings to work and home interiors, “We wanted to create something that wasn’t just about the passing hours but something that could evoke a deeper connection with the natural world. Our intention was to bring a sense of tranquility and contemplation into people’s spaces,” adding, “We hope it serves as a gentle reminder of our interconnectedness with the natural world and the importance of finding moments of calm within these larger, more gradual cosmic rhythms.”

Terri C Smith is a curator, writer, and professor who has developed innovative, critically recognized contemporary art programs in the U.S., foregrounding sociopolitical themes and conceptual art practices.

The Author's cat is coincidentally named "Moon" after the song "Moon River".

The Author's cat is coincidentally named "Moon" after the song "Moon River".

[1] Image labeled fair use and retrieved from: https://loc.getarchive.net/collections/the-moon-in-japanese-art

[2] Chris Koller. “Themes: The moon Through the Eras.” https://www.asianartscollection.com/id/Themes%3A-The-moon-Through-the-Eras/17

[3] https://www.nippon.com/en/features/jg00115/ (no author listed, Sept 9, 2018)

[4] https://www.aboutmybrain.com/cards/goddesses-of-the-world-oracle-deck/mama-quilla

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_lunar_deities paraphrased from Eugenio, D. L. (2007). Philippine Folk Literature: An Anthology. University of the Philippines Press, pp. 21-22.

[6] Haely (Haeyoon) Chang. “Korea’s moon Jars—Transported, Transfigured, and Reinterpreted.” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, 2018, Vol. 92, No. ¼, pp. 36-49.

[7] Colleen Boyle. “You Saw the Whole of the moon: The Role of Imagination in the Perceptual Construction of the moon.” Leonardo, 2013, Vol 46, No. 3, pp. 246-252.

[8] Ann Zumwalt, “Galileo’s moon-- Then and Now” http://galileo.rice.edu/lib/student_work/astronomy95/moon.html

[9] Paul Glynn, 2021. “William Blake: Biography offers glimpse into artist and poet's visionary mind.” BBC online: https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-57419544

[10] Image labeled fair use and retrieved from: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003665540/

[11] Andrew Green. “William Blake on the moon.” gwallter blog, 2019. https://gwallter.com/art/william-blake-on-the-moon.html

[12] https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/438417

[13] For more on this work, visit Montclair Art Museum: https://www.montclairartmuseum.org/george-inness-adrienne-baxter-bell

[14] For more information about this work, visit Christie’s https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6419585

[15] Nancy Weekly, 1998. https://burchfieldpenney.org/art-and-artists/artwork/object:l2010-001-044-sun-and-rocks/

“Sun and Rocks was enlarged and repainted over several years. In 1948, Burchfield ‘put into the sun all the devastating destroying power of that ‘star’ that I feel on a March Sap day.’ The cruciform star glorifies Christian hope, hinting at both the star of Bethlehem which signifies the birth of Christ, and the cross of Calvary, which signifies his crucifixion and resurrection. Burchfield said, ‘The Bible calls it the ‘great day star'... so brilliant and its blaze of light so strong it becomes a diamond shape to me.’ The image stands for Burchfield's relatively recent "enlightenment"—his conversion to Lutheranism four years earlier.”

[16] Victoria Valentine, 2019. Culture Type (blog).

[17] Caitlin Dover, 2015. “Choosing the Moon: Examining On Kawara’s Paintings of the Lunar Landing Dates.” https://www.guggenheim.org/articles/checklist/choosing-the-moon-examining-on-kawaras-paintings-of-the-lunar-landing-dates

[18] https://www.artsandcollections.com/the-qlocktwo-universe-from-germany-to-the-world/

[19] Alex J. Taylor, “The Painting.” Images of Dove and O’Keeffe can be found at https://www.tate.org.uk/research/in-focus/gift-kenneth-noland/the-painting

[20] https://whitney.org/collection/works/11686